Artifacts from Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King, and Gandhi are coming to Philly for America's 250th

Published in Lifestyles

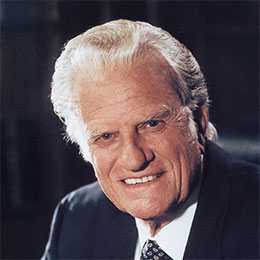

PHILADELPHIA -- Kenneth B. Morris Jr.’s family treasures have always been American treasures.

Morris, 62, is the great-great-great-grandson of abolitionist and orator, Frederick Douglass, and great-great-grandson of famed educator and founder of Tuskegee Institute, Booker T. Washington.

Growing up surrounded by the relics of his famous ancestry — including Douglass’ books, photos, letters, reading glasses, and Stradivarius violin — Morris once took Abraham Lincoln’s ivory-handled walking stick, gifted to Douglass by the late president’s widow, Mary Todd Lincoln, to elementary school show and tell.

“Nobody believed me,” Morris laughed.

Morris is proud that a piece of that family legacy is soon heading to Philadelphia.

Artifacts to commemorate 250

As part of its major exhibition marking the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence in 2026, the Museum of the American Revolution will display a rare, first-edition printing of Douglass’ famous speech: “What, to the American slave, is your Fourth of July?”

Delivered on July 5, 1852 in Rochester, New York, it is celebrated as a sardonic evisceration of the hypocrisies of American democracy.

“It is one of the greatest speeches in American history,” said Morris, cofounder and president of the Frederick Douglass Family Initiatives, a nonprofit based in Rochester, New York, that combats racism and human trafficking.

The speech is just one of dozens of new objects the museum will soon display in honor of America’s 250th, also known as the Semiquincentennial. The museum’s first Semiquincentennial programming, ”Banners of Liberty,“ opens April 19, the 250th anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the first military engagements of the Revolutionary War. Featuring 16 original Continental Army and American Militia flags — and one of the earliest examples of the Stars and Stripes known to exist — the exhibit represents the largest gathering of Revolutionary War banners since the war’s end in 1783. It runs through Aug. 10.

In October, the museum will debut ”The Declaration’s Journey,“ a special exhibition exploring the enduring power, complexity, and unfilled promise of the famous freedom document. The exhibit, which runs through Jan. 3, 2027, has been billed as one of the key public events in Philly’s celebration of the Semiquincentennial.

The Revolution museum, which has welcomed 1.5 million visitors and built a $100 million endowment since its opening in 2017, has long prepared for the Semiquincentennial as a natural moment to shine.

“The kind of gravitational force that will come as a result of the 250th, it’s like when you use the moon to slingshot a satellite into outer space,” said R. Scott Stephenson, president and CEO of the Revolution Museum. “That’s the opportunity that this moment in Philadelphia will have for us, not just through increased visitation, but just the organic rise in attention and interest.”

On an average year, the museum sees about 175,000 visitors.

“My dream is to be able to say we got 250,000 visitors for the 250th,” he said.

250,000 visitors for the 250th

To bring the story and lasting legacy of the declaration to life, the museum spent five years amassing roughly 120 rare documents, art, and artifacts from cultural and historical institutions and private collectors and families across the country.

In recent months, that historical trove has begun to fill the museum’s sprawling collections storage rooms, as conservators prepare the materials for exhibit. By October, it will include objects ranging from Douglass’ speech to the metal prison bench from which the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. composed his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” in 1963. The type from the printing press that printed the 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic. A makeshift ballot box made from blueberry crates used by women in Vineland, New Jersey, to cast illegal ballots in 1868. A copy of the July 6, 1776 Pennsylvania Evening Post, the first newspaper to print the Declaration of Independence. And a copy of the paper’s previous issue, printed days earlier, which included advertisement for the sale of “a negro boy, about four or five years of age.”

“We sought to create a rich and dynamic display,” said Matthew Skic, director of collections and exhibitions of the Revolution Museum.

Many of the new artifacts carry the weight of history, but also the freedom stories and intimate histories of the families that long preserved them.

“We looked for artifacts and artwork connected to specific individuals in the creation of the United States Declaration or international declarations,” Skic said.

A letter from Gandhi

One of Ila Good’s earliest memories is sitting in Mahatma Gandhi’s lap.

By 1928, the legendary Indian civil rights leader had grown close to Good’s grandparents, all members of the same tight-knit Indian community in South Africa, where Gandhi lived before returning to India to organize nonviolent resistance against British colonial rule.

Back in India, Gandhi developed a father-like relationship with Good’s mother, Tara, named for the Sanskrit word meaning, “star,” and whose own father had remained in South Africa. He often stayed at the family estate in coastal Gujarat during turbulent times, like one of his final fasts protesting Hindu atrocities against Muslims.

“He was defying the British and started to fast, which was his weapon against fighting the British.” Ila Good said. “So he fasted, and he was in our family home.”

He became a grandfatherly figure to Ila and her sisters.

“He was a very busy man, surrounded by all kinds of important visitors, but he would always find time to show some affection,” she said.

On the road, he would write Tara Good, instructing her on how to take care of her health.

And a caring father, he chided Tara when she did not write back.

“I have had no letter at all from you,” he began one letter in 1928, going on to explain that he would be sending her a charkha, a wheel to spin homespun cloth rather than relying on British manufactured goods. The charkha became a powerful symbol of the Indian independence movement.

“There must be at least one spinning wheel,” Gandhi told Tara Good.

It is that family artifact that Ila Good, who lives in Northern Virginia, is loaning to the museum to be displayed for the entirety of “The Declaration’s Journey.”

For now, it is still displayed in her home alongside another of Ila Good’s most treasured possessions: a small, silver box containing ashes collected from Gandhi’s funeral pyre following his assassination in 1948.

“But that’s another story,” she said.

The suffragists

Growing up, when visiting her grandmother’s home in Greenwich, Conn., Coline Jenkins thought of the big, sprawling, shadowy attic as the “Valley of the Queens” because that’s where three generations of the family’s artifacts from the women’s suffrage movement were stored. Jenkins, who lives in Greenwich, is the great-great-granddaughter of the prominent 19th century leader of the women’s rights movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

In 1848, Stanton, and Philadelphia abolitionist, Lucretia Mott, held the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls, New York, launching the women’s rights movement. It was there that Stanton principally authored The Declaration of Sentiments, a monumental woman’s right document she modeled on the declaration.

It was the beginning of a family movement.

Stanton’s daughter, Harriot Blatch, became a leader of the suffrage movement and her granddaughter, Nora Stanton Barney, was among the first women to graduate with a civil engineering degree in the United States.

And all that history was in grandma Nora’s attic.

“Up in the attic were all of Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s works, her books, photographs, letters, the furniture,” said Jenkins, 73, who recalled playing with a foldable soapbox that Nora Stanton Barney designed and carried so she could speak on corners and in parks in favor of the 19th Amendment.

Nora Stanton Barney would tell how her grandmother sat her in lap and listed the rights and wrongs of womanhood.

“You could do a nursery rhyme, or you could read a book, but she explained the rights and wrongs of womanhood,” Jenkins said.

Among the furniture in the attic, was also a writing desk Stanton kept in her Tenafly, New Jersey, home when she began working on the three-volume History of Woman Suffrage with Susan B. Anthony. Jenkins is loaning it to the museum for the full run of the exhibit.

“It means so much to me,” Jenkins said through tears. “The exhibit is a reminder of who we are, where we came from and where we’re going.”

Frederick Douglass’ family legacy

As long as he can remember, Kenneth Morris knew that there was something special about his family legacy. But it wasn’t until he was about 5 or 6 and started seeing the images of his famous ancestors memorialized on statues and stamps that he realized he carried the blood of American history.

As a child growing up in Maryland and California, Morris recalls visiting the family home in Highland Beach, Maryland, that Frederick Douglass’ son, Charles, built after being turned away from a restaurant at a nearby resort because of his race. The house was built and designed as a retirement home for Frederick Douglass, but he died before it was completed. Still, it included a second-story porch that Frederick Douglass had designed. He had wanted it so he could look over the Chesapeake Bay to the Eastern Shore of Maryland — the land where he had once been enslaved.

Morris recalls family photos and letters from Booker T. Washington, whose granddaughter, Nettie Hancock Washington had married Dr. Frederick Douglass III, great-grandson of Frederick Douglas. And how each summer, his great-grandmother, Fannie Douglass, would take inventory of family relics, laying out the artifacts across the foot of a bed and telling how Frederick Douglass loved giving grandchildren horseback rides and letting them braid his hair.

“He would get down on all fours and give them horseback rides and let them use his great, big white hair for the reins,” Morris said, with a laugh.

Then, he said of his legendary lineage: “I can tell you that there was love and humility and forgiveness and empathy and all of those things were passed down through the family.”

Morris said it is fitting that the famous speech Douglass’ gave all those Fourths of July ago will be included in the museum’s Semiquincentennial major exhibit.

“He called out the hypocrisy of a nation that would espouse the ideals of freedom, liberty, justice and equality, while enslaving people of African descent on its blood drenched soil,” he said. “But then, as he did in just about all of his speeches, he ended on a note of hope.”

©2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer, LLC. Visit at inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments