You look like a Michael: What research shows about how names shape your life

Published in Slideshow World

Subscribe

You look like a Michael: What research shows about how names shape your life

Names matter—or do they? They are the first things we receive. They reflect our parents' hopes or honoring heritage; they are formative. Our name will be spoken to us repeatedly, in praise, anger, and all tones between. It's usually the first thing people know about us. For some, it can be something to live up to or something to live down.

We can change our names, shorten them, modify them, resist them, or inhabit them. They become, for many, a crucial part of who we are, but do they control our destiny or shape our character? If you had a different name, would you be a different person? You are more than just your name, of course, but in powerful ways, it influences your experience; it shapes people's assumptions about you, like a book cover or the musical key to which the score of your life has been set.

For this article,Spokeo usedSocial Security Administration data and academic research to explore the powerful, unexpected, and surprisingly subtle connections between names and how they can shape your life.

Over time, researchers have found a strong link between names and people's personalities, self-image, and sense of belonging. In some cases, an unusual name may link to creativity and unexpected professions. Some names are seen as "warm" or "kind," while others invoke more negative connotations,said Michael E. W. Varnum, associate professor at Arizona State University, where he heads the social psychology area. He directs the Culture and Ecology Lab and researches how ecological factors influence human cognition, behavior, and culture.

"We know that people reliably make assumptions about things like ethnicity and social class based on names," Varnumtold Stacker. "Names are something that people often put a lot of thought into choosing, they can be a way to express values or identity or hopes for one's child."

Names are, of course, just one of many factors that can influence a life; they are meaningful and influential but not determinative in and of themselves. For instance, Varnum said, "We may be more likely to move to cities that share the first letter of our names, or if you are named Dennis, you are somewhat more likely to be a dentist, or that people named Carpenter are more likely to be carpenters." This phenomenon of linking professions and behavior to names is known as nominative determinism.

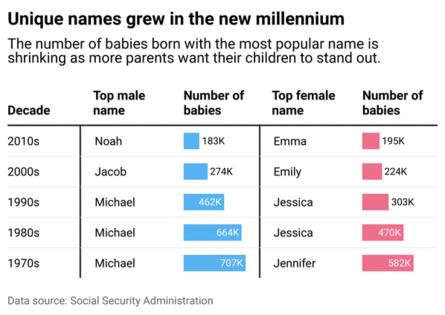

Over the past generation, baby names in the U.S. have been increasingly unique, leading to a relative decline in typically favored names. In contrast, for the three consecutive decades prior to 2000, the reigning name for boys was a single one: Michael (see byline). In this writer's purely unscientific, anecdotal experience, being a part of such a crowded cohort can produce a peculiar dissociation, given the preponderance of classmates and peers sharing it. (Yes, I hear it being called, but chances are it isn't for me.)

Visit thestacker.com for similar lists and stories.

Top names by decade

Editor's note: The Social Security Administration collects data on baby names based on a binary understanding of sex and gender; however, we recognize that names aren't inherently gendered.

Varnum became interested in studying naming trends because public naming records were available, and they could help answer elusive questions on "more direct psychological measures, like individualism or conformity." In contrast, data from traditional measures, like questionnaires or experiments, may be limited in time or scale.

"In my work, I've shown, for example, that people are less conformist in their naming practices in places that were more recently frontiers," Varnum said. In addition, "Within the U.S., adecline in the frequency of people receiving popular names over the past century or so appears linked to things like rising levels of wealth and decreasing pathogen threat." He suggests these factors may encourage people to pursue autonomy and uniqueness more.

Whatever the explanation, parents in the U.S. seem to be increasingly favoring names that might help their child to "stand out" from their peers. At the same time, gender-neutral names have also become more common, starting to rise in popularity in the '90s, according to Names.org.

Michael, while no longer king for boys, was still a respectable #7 in the 2010s and #2 in the 2000s. Some parents still favor tradition over novelty. Curiously, the same cannot be said for the most popular girls' name for three decades leading up to 2000—Jessica, which fell to #175 in the 2010s.

And then there are the names that, in the popular imagination, have become insults: the memeable monikers of "Karen," "Chad," or "Kevin." Varnum explains, "People with names that are currently disliked in the U.S, like Chad or Karen, probably bear some of the weight of the negative stereotypes and associations folks have with those names. And prior work does find that we feel more warmly, for example, towards Elizabeths than Mistys."

Rightly or wrongly, names are a type of shorthand for expressing a sense of self, establishing connections, marking national and ethnic affiliations, and becoming targets for stereotypes and prejudice. For instance, Varnum said, "People sometimes also assume that those with names more common in African American communities might be of lower status or less competent."

Aaron Hall, CEO of the San Francisco-based branding company Emphatic, recently wrote about the connection between baby naming and company branding: "Naming a baby is a joyous, significant event. By applying some tried-and-true branding principles, you can approach the process with confidence and creativity."

Offering the caveat that he hasn't personally named a human, Hall nonetheless said landing on the right name, be it for a baby or a company, can be a fraught and stressful process. "It's important for that baby and brand to develop their own sense of self and characteristics that define who they are," Hall told Stacker. "The name doesn't have to anchor them to the original intent or connotations."

Story editing by Carren Jao. Additional editing by Elisa Huang. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Spokeo and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Comments