Trump's tariff wars leave US small business with nowhere to hide

Published in Business News

American companies of all sizes are on edge over President Donald Trump’s tariffs, but it’s arguably small business that is most exposed.

Many smaller firms say they’re having to hike prices, freeze expansion plans or absorb a hit to already-thin profit margins as import bills climb. Such businesses employ half the U.S. workforce, so how they cope with Trump’s ramped-up trade war will be crucial to the wider economic impact.

In Florida, Jay Foreman has already felt the bite. He’s chief executive of Basic Fun Inc!, which designs and markets toys like Care Bears and Tonka trucks — and his imports from China were spared from Trump’s first-term tariffs, which focused more on materials and machinery than consumer goods.

But not this time. Foreman says his prices with vendors and customers were already locked in through the third quarter when a new 10% China levy landed this month. For now he has no choice but to absorb the costs, which could wipe out almost one-third of this year’s profit margin.

After that, if there’s no U.S.-China deal to remove tariffs, his options include pressuring suppliers to charge less, accepting smaller profits, and raising toy prices just in time for the holidays.

The China tariff is the only new one on the books thus far in Trump’s second term — but with many more slated over the coming weeks, the floodgates are about to open. Trump says this protectionist policy will revive American industry. Many analysts worry it will rekindle inflation instead, and drag down a U.S. economy that’s been growing strongly.

“We’re just all going to have to deal with it and keep our heads down and hope it all works out,” Foreman says — adding that Trump won the election promising to bring prices down, and his administration should consider whether tariffs have the opposite effect.

‘Abundantly clear’

That’s one of the big unknowns about Trump’s trade plans, especially after U.S. consumer prices began the year with an unexpected jump. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell acknowledges that tariffs could change the inflation picture, though he’s walked a careful line when asked how they might affect interest-rate decisions.

Many small businesses don’t have the option of soaking up tariff costs: they just have to raise prices. That’s the case at Field Fastener, according to Chief Executive Jim Derry. The firm, based in Rockford, Illinois, sells bolts, screws and other components — largely sourced from China and Taiwan — that are used to make all kinds of things, from football helmets to elevators. “Our customers’ products are in your everyday lives,” says Derry.

Those same customers are now on notice that prices are headed up. “We’ve made it abundantly clear,” Derry says. “If tariffs are increased or added, we cannot absorb them.”

Passing on a cost increase isn’t always simple. What if buyers balk at the higher price? That’s less of a headache for the biggest firms, who as dominant players in their markets tend to have what economists call pricing power — the ability to make hikes stick without losing customers.

It’s not working that way for Pervaiz Lodhie, president of California-based LEDtronics, which designs and builds lighting products. They’re used in planes and hospitals, and components come from around the world, including China.

Lodhie says many of his customers have been with the firm for decades, but that doesn’t mean they’ll pay whatever he asks. “I have a major, 40-year customer that won’t allow me to increase my prices. I’ve told them this is the best I can do,” he says. “I may lose the customer.”

‘We are paralyzed’

Along with inflation, another key tariff question is how business investment will be affected. The concern is that companies will be reluctant to build factories in America and add jobs — the ultimate purpose of Trump’s trade policy — until they have a clearer idea of how much they’ll have to pay to import machinery, parts or materials.

That’s an issue for corporate giants — General Motors won’t “spend a large amount of capital without clarity,” Chief Executive Mary Barra has said — and, at the other end of the scale, for Todd Adams at Sanitube too.

The family-owned, Florida-based firm makes stainless steel tubing, valves and fittings for food manufacturers. It sources materials from a range of countries, and employs some 20 people. Sanitube has put expansion plans on hold, Adams says, because there’s no telling how much his bills will increase as a result of tariffs — and he needs to conserve cash just in case.

He’s already on the hook for the 10% China duty, and may well be exposed to two separate tariffs due to take effect early March, on metals and Canadian goods. “We are paralyzed as a company,” he says. “Until we have an idea of what tomorrow, next month or this year holds, we’re just sort of in a holding pattern.”

Sanitube got landed with an unexpected tariff bill of a couple hundred thousand dollars in Trump’s first-term trade war, Adams says, because it had a large order from China that had already been purchased and shipped when steel and aluminum tariffs were imposed. The administration denied requests for an exclusion or reimbursement.

Back then, since tariffs were concentrated on China, many importers sought to avoid them by buying elsewhere. Vietnam and Mexico, which saw exports to the U.S. surge, were among the big beneficiaries.

This time around, Trump is casting his tariff net wider — the goal isn’t “friendshoring” supply chains in sympathetic countries, but boosting output in the U.S. itself — so repeating the trick might be harder.

‘You’re stuck’

Still, it’s an option Darren Klein is looking at. He’s chief operating officer at Poly Craft Industries in New York, which makes packaging material like pouches and bags for well-known consumer brands. It produces in the U.S. using materials sourced from China among others.

“10% is enough to drive a change in behavior,” Klein says of this month’s tariff hike. “It would most likely push us to choose a different source. We don’t really want to have to increase pricing if we can avoid it.”

It’s generally harder for smaller firms to adjust their supply chains in order to avoid tariffs, says Claire Reade, a senior counsel at Arnold & Porter and former assistant U.S. trade representative for China affairs and chief counsel for China trade enforcement.

“You’re a little guy — you don’t have the capital to go off and march into a completely different country and try to start over,” Reade said. “You’re stuck.”

Another thing the little guys lack is lobbying power. After Trump launched the trade war in his first term, a “bewildering array” of businesses were able to win tariff relief, according to the Brookings Institute. The upshot was “heavy costs on small- and medium-sized enterprises that were ill-equipped to jump through the bureaucratic and political hoops.”

‘My year’s supply’

As the trade threat grew through the end of last year, U.S. businesses and consumers did what they could to get ahead of it. A surge in imports, and in sales of big-ticket items like cars and home appliances, suggest a nationwide bid to frontrun the Trump tariffs.

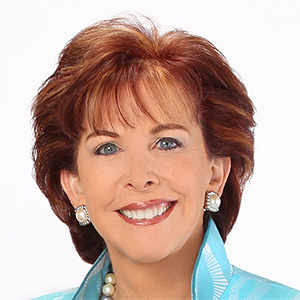

That wasn’t possible for every small firm — Foreman, the Florida toymaker, said it wouldn’t work in his industry because the whims of children change too fast — but Margo Clayson managed to pull it off.

Her business — The Mighty Microgreen, based in Inkom, Idaho — sells kits for people looking to grow small vegetables indoors. Clayson says she stockpiled materials from China in recent months, anticipating that the next phase of trade war might hurt her. She ordered 30,000 heavy-duty plastic trays, and got them before Trump’s new 10% China tariff took effect. It saved her about $1,200.

“I kind of figured that’s my year’s supply and hopefully things will calm down,” she says. If they don’t, Clayton sees a threat to her business because she’d likely have to raise prices. She says she explored sourcing the trays domestically, but concluded it would be too costly.

‘It is what it is’

Of course, Trump’s agenda isn’t all about tariffs, even if it looks that way some days. There’s plenty in his platform — like his promises of lower taxes, cheaper energy and a purge of bureaucratic red tape — that’s gotten small business cheering.

After Trump won November’s election, an index of small-business optimism jumped to the highest in more than six years. But it fell back a bit last month, when the same survey also showed the steepest drop in capital-spending plans since 1995.

In the furniture industry, which relies on housing sales for a big chunk of business, perhaps the biggest obstacle right now is mortgage rates of around 7%. That made 2024 a tough year for companies like Kevin Charles Fine Upholstery, which produces mostly in the Tupelo, Mississippi area — a historic furniture-making region — and supplies the City Furniture chain. It had to trim staff by almost one-fifth through retirements and attrition.

Adding a 10% tariff on top of the industry’s current funk won’t help. A small share of cutting and sewing for the firm’s lower-end pieces is done in China, and so subject to this month’s new tariffs.

“Will it make some of our products go up? Yeah,” says the company’s president, Rusty Berryhill. But there’s a silver lining: the tariffs will give U.S.-made furniture an advantage over finished pieces from China, Berryhill says.

“It is what it is,” he concludes. “We’ve got to run our business accordingly.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments