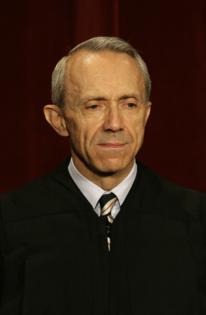

Noah Feldman: David Souter set an example for the Supreme Court

Published in Op Eds

David Souter, the former U.S. Supreme Court justice who died at 85 on Thursday, was sometimes mistakenly thought to have turned into a liberal after being nominated by President George H.W. Bush on the expectation that he would be an ideological conservative.

History will show the opposite: Souter was among the most consistent, principled justices ever to have sat on the Supreme Court in its 235-year history. His jurisprudence was steeped in the value of precedent and the gradual, cautious evolution of the law in the direction of liberty and equality.

A New Englander to the core, he said what he meant and meant what he said. At a moment of unprecedented threat to the rule of law, Souter’s career stands as a model of judicial strength and resilience tempered by modesty and restraint. If the court follows his example, the Republic will survive even the serious dangers it is facing now.

At his confirmation hearings, relics of another time, Souter spoke openly of his admiration for Justice John Marshall Harlan II, known for his explanation that constitutional liberty is derived from a “tradition” that “is a living thing” and cannot be “limited by the specific guarantees” of the text.

The key to Souter’s judicial philosophy was the idea, derived from the common law method of precedent and also linked with the conservatism of Edmund Burke, that the rule of law works best to protect us when it proceeds by slow steps attuned to social change, not by leaps forward or backward that produce backlash and end up rejected.

The most famous expression of Souter’s precedent-based view came, with characteristic modesty, in a joint opinion that he cowrote with Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy in the 1992 case of Planned Parenthood v. Casey. The Casey decision upheld the abortion right laid down in Roe v. Wade on grounds of stare decisis, respect for precedent, even as it distanced itself from Roe’s logic.

The justices explained that overturning Roe “would seriously weaken the court’s capacity … to function as the Supreme Court of a Nation dedicated to the rule of law.” In a sentence that exemplifies Souter’s complex-yet-subtle style, the justices wrote that the court’s power lies “in its legitimacy, a product of substance and perception that shows itself in the People’s acceptance of the judiciary as fit to determine what the Nation’s law means and to declare what it demands.”

Broken down into its component parts, what this all-important passage means is that the Supreme Court can only protect the rule of law if it is perceived as legitimate by the people. That is because the people are the ultimate authors of the Constitution and ultimately responsible for making sure it is followed. Judicial legitimacy, for Souter, comes from the judicial method, which is to move slowly and not break things.

The conservative majority of the current Supreme Court rejected this logic when it overturned Roe, and with it, Casey. That breaking of precedent weakened the court’s legitimacy, as Souter predicted it would. Now that same Supreme Court must rely on its weaker legitimacy to stand up to save the rule of law.

Souter would have an answer: The court can and must return to precedent, because that body of judicial opinions going back in time is the only basis on which the court can rely when saying that its interpretation of the Constitution is best. The court cannot and must not insist that its interpretation is correct because it is certainly or objectively true. Rather, the weight and legitimacy of the court’s interpretation of the Constitution comes from its acknowledgment of its own uncertainty.

That is a complicated thought, but it is the essence of Souter’s profound insight into constitutional judgment. In a commencement address he gave at Harvard University after retiring from the court, Souter rejected the false certainty of originalism, which he ascribed to the false aspiration to certainty. Where he differed from the originalists like the late Justice Antonin Scalia, he said, was in Souter’s “belief that in an indeterminate world I cannot control it is possible to live fully in the trust that a way will be found leading through the uncertain future.”

The justices must interpret “constitutional uncertainties” by “relying on reason that respects the words the framers wrote, by facing facts, and by seeking to understand their meaning for the living. He concluded: “That is how a judge lives in a state of trust.” The trust, in other words, comes not from inherent certainty but from following the path the living Constitution has followed, a path of evolving precedent.

Personally, Souter’s self-conception paralleled his philosophy of living tradition. It was sometimes said that Souter was a man of the 18th century. That was almost, but not precisely, correct. He abjured technology and lived much of his adult life in a centuries-old family farmhouse in Weare, New Hampshire (population 9,092). He worked seven days a week, allowing himself to arrive late in chambers on Sunday morning only because he had attended Episcopal Church. He never wore a coat in Washington, maintaining that it was never cold enough to warrant it, even while standing for hours in the snow awaiting the casket of Justice Harry Blackmun. He ate nothing but an apple and yogurt for lunch, ran miles every day in all weather and loved books as much or perhaps more than he loved people.

Yet in fact, in his mind and in his soul — which were in his case almost the same thing — Souter was, to a remarkable degree, a man of the late 19th century, the time when the ideals and assumptions of the founders’ America ran headlong into modern democracy, modern industry and modern capitalism. His favorite authors, whose literary style influenced his distinctive judicial opinions, were the novelist Henry James (1843-1916) and the historian-statesman Henry Adams (1838-1918). He wrote his senior essay as a philosophy undergraduate on the thought of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (1841-1935); he was awarded his degree summa cum laude for it before going off to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar.

Like those great American thinkers, Souter devoted himself to trying to figure out how to maintain continuity with the ideals of the American past while acknowledging vast discontinuities in contemporary reality. If, in the distant future, his own diaries become public, I expect those who have the privilege of reading them will marvel at the similarity of the intellectual and spiritual challenges faced by James, Adams, Holmes and Souter, born a hundred years later than the foundational figures with whom he identified.

Clerking for Souter was the privilege of a lifetime. His kindness, his charm and his elegance of character were all palpable beneath the formidable facade of New England reserve. Sitting in his office exchanging ideas and stories with him, as the light faltered, I knew, as I have rarely known anything before or since, that I was in a chain of transmission that went back to the Puritan fathers who were his literal ancestors and my metaphorical ones.

He was the best and wisest man I have ever known.

____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Feldman is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A professor of law at Harvard University, he is author, most recently, of “To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People."

____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments