COUNTERPOINT: Conventional wisdom behind birthright citizenship is flat error

Published in Op Eds

Once upon a time, doctors were convinced that using leeches and drawing the blood of patients cured illness. No matter how widely accepted that error was, leeches didn’t cure anything. The same is true for the belief that anyone born in the United States automatically becomes an American citizen.

Please stick with me; I used to think it was true. Then I read the Supreme Court cases purportedly saying the 14th Amendment automatically makes a child born in the United States an American citizen.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark is a Supreme Court case from 1898 that supporters of automatic birthright citizenship say settled the matter.

It didn’t, not even close.

Wong Kim Ark addressed a very narrow legal question: whether a child born in the United States to lawful permanent residents of Chinese descent was entitled to citizenship under the 14th Amendment. The case did not, despite the conventional wisdom over decades, reach the question of whether children born to parents illegally in the United States were entitled to citizenship under the amendment.

In other words, it did not answer whether those not subject to the political jurisdiction were entitled to birthright citizenship. The court ruled in favor of Wong Kim Ark, concluding that the children of lawful permanent residents who are “domiciled” in the United States are entitled to birthright citizenship.

Wong Kim Ark did not address the question of whether children born to individuals who are unlawfully present in the United States qualify for birthright citizenship, no matter how many activists say otherwise.

So, how did the train get rolling where birthright citizenship became commonly accepted? Like so much that goes wrong, it all started with a bureaucrat. It wasn’t until the second half of the 20th century that State Department officials began issuing passports to anyone born in the United States.

At some point in the history of medicine, some quack thought bleeding patients with leeches cured illness. At some point in the 20th century, a bureaucrat in Washington decided to start issuing passports to anyone born in the United States.

The 14th Amendment has a clause that grants citizenship to people born in the United States “and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” The Supreme Court in Wong Kim Ark made it clear that “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” has meaning. There are limits to who can become an American just by being born on United States soil.

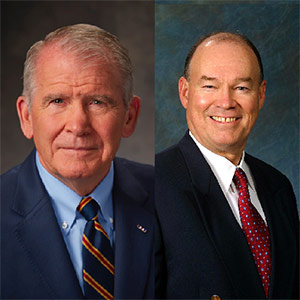

I have filed an amicus brief in the Supreme Court for former Attorney General Edwin Meese III. The Public Interest Legal Foundation represents Meese because this issue is central to our nation. The electorate’s composition has changed dramatically in the last half-century since the State Department started bleeding the patient.

This case will boil down to the difference between political and territorial jurisdictions. The authors of the 14th Amendment explicitly, on the floor of the Senate, said citizenship was to extend only to those subject to the political jurisdiction of the United States and not a foreign power. Sen. Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, a key architect of the amendment, explained that “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” meant “not owing allegiance to anybody else.”

In contrast to the authors of the 14th Amendment, open borders advocates want “subject to the jurisdiction” to mean territorial jurisdiction. That means “step on United States soil and give birth, instant American.”

That view is an outlier globally. One misguided bureaucrat shouldn’t count more than the authors of the 14th Amendment.

____

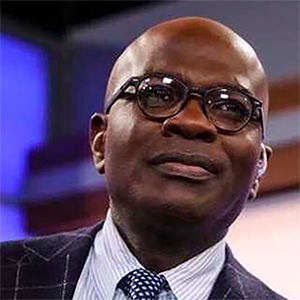

ABOUT THE WRITER

J. Christian Adams is the president of the Public Interest Legal Foundation and a commissioner on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. He wrote this for InsideSources.com.

___

©2025 Tribune Content Agency, LLC

Comments