Adrian Wooldridge: Making America healthy should be a bipartisan challenge

Published in Op Eds

There are many intriguing mansions in the great house of MAGA but perhaps the most intriguing of all has its own name: MAHA or Make America Healthy Again. America undeniably suffers from a serious health crisis: Almost half of Americans have high blood pressure, three-quarters are obese or overweight, and 15% have type 2 diabetes. Previous attempts to improve these figures have been frustrated, despite the liberal application of the world’s best brains. Can America’s eccentric new health and human services secretary succeed where so many of his sensible predecessors have failed?

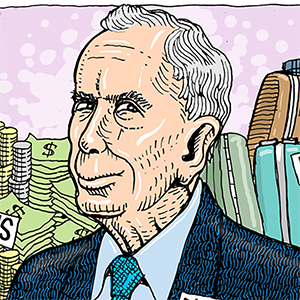

There are obvious reasons for doubt. Donald Trump’s pick for the job is, to put it mildly, an oddball: a scion of the Kennedy dynasty, a reformed heroin addict and womanizer, a devotee of odd diets such as raw milk, and a manchild given to strange practical jokes such as dumping a dead bear cub in Central Park, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is that worst of all combinations, a crank and a lawyer.

He is a vaccine skeptic who has repeatedly claimed that vaccines are linked to autism, a claim for which there is no generally accepted evidence. This might be regarded as a disqualification for even an entry-level job at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, given that vaccines have done as much as anything to tackle horrible diseases such as polio and improve life expectancy. He is also more skilled in annoying giant organizations than running them, let alone running one that spends more than $1.7 trillion a year.

Kennedy repeatedly insisted in his confirmation hearings that he is not a vaccine denier and that his skepticism is focused on mercury. He promised to enforce good practice. But his first few weeks in office have been disappointingly lethargic, in contrast to the focused energy coming from the White House. He has devoted a lot of time to defending his questionable handling of a serious measles outbreak in a Texas district populated by anti-vaxxers. An elusive figure in his department, he has nevertheless found time to visit Florida and pose for a photograph with Russell Brand, a disgraced British comedian. Kennedy remains curiously tanned given the absence of sun in the capital.

The forces of inertia are vast. These begin with the organization of Washington. The U.S. Department of Agriculture is under the thumb of Big Food, which, by design and habit, maximizes the production of staple foodstuffs, including foods that can be very bad for you, such as sugar, corn syrup, salt and fat, and which provide the building blocks of ultra-processed food. Kennedy’s department focuses on producing medicine and research. The result is a perverse equilibrium: One department creates sick people and the other fixes them, thereby perpetuating America’s underlying health problems: a “sick care” system rather than a “health care” system. The most important tools that Kennedy needs to achieve his goals are in the hands of the secretary of agriculture.

The special interests also have an unbroken record of resisting reform. Food and soft drink companies have stymied attempts to improve Americans’ diets with a ruthlessness that would impress the National Rifle Association. Coca-Cola Co. and PepsiCo Inc., working through the American Beverage Association, have blocked attempts by centrist reformers to impose higher taxes on sugar or limit the size of the drinks for sale.

Yet Kennedy’s very eccentricity may prove to be a great asset given the failure of his sensible predecessors. Taking on the status quo is the leitmotif of Kennedy’s life. He is also right about one big thing: America’s best chance of improving health care lies in tackling chronic diseases such as heart-disease and hypertension, both of which are linked to poor diet and exercise. HHS has tended to focus on high-level research because that is where status in the medical profession lies. But the big gains lie in improving America’s diet and lifestyle rather than churning out more research papers.

Kennedy also has something that none of his predecessors has had: a movement. For centrists, health-care reform has been a matter of experts telling the people what to do, a model that was tested to destruction by Anthony Fauci during the pandemic. RFK is the head of a movement that involves ordinary Americans on the left and the right pledging to improve their own health, often in response to serious health problems. His MAHA crusade originally took off among left-wing activists, particularly “crunchy moms,” who concluded that America’s food-and-health system was broken. Now MAHA also has enthusiastic supporters in Deep Red America such as the governor of Arkansas, Sarah Huckabee Sanders.

The combination of institutional and movement power gives RFK two ways to achieve his aims. He can use his responsibility for food safety to crack down on the chemicals that companies nonchalantly add to food. (Visiting Europeans are often surprised by how brightly colored U.S. food is, only to become outraged when they discover that some standard ingredients are banned in the EU.) He can also put the full weight of MAHA behind moves to prevent people from spending food stamps on sodas and other forms of junk food, despite the formal control wielded over food-stamp programs by the Department of Agriculture.

For too long good health has been associated with liberal do-goodery and top-down expertise — and Red America has seen Big Macs and Big Gulps as weapons against digestive elitism rather than as threats to their cardiovascular systems. The MAHA movement is relinking good health to a bottom-up tradition of self-help — a tradition that has thrown up a long line of benevolent cranks such as the Kellogg brothers, who started the eponymous cereal companies, and that currently flourishes on the internet. Vani Hari, the “Food Babe,” an internet influencer with more than two million followers on Instagram and an ally of RFK, has warned food companies that “if you’re an American company poisoning us with ingredients you don’t use in other countries, we’re coming for you.”

It is also scrambling the battle lines in American politics. Sanders is one of the most enthusiastic supporters of preventing people from using food stamps to purchase soda even though such purchases represent significant revenue for Walmart Inc., her state’s flagship employer. Trump has told RFK to “go wild” on food despite the president’s own enthusiastic consumption of Diet Coke and Big Macs and the high correlation between localities dominated by chain restaurants and Trump voters.

With the MAGA Right and the Crunchy Left on RFK’s side, the most stubborn resistance to MAHA is coming from the center, particularly from the credentialed class that loathes Trump and dominates the healthcare complex. More than 15,000 doctors signed an open letter lobbying against his confirmation by the Senate for example. RFK’s anti-vax history certainly needs to be condemned. And some of his woo-woo beliefs deserve contempt. But does it make sense to spend the next four years, or however long he is in office, dwelling on his shortcomings and failures? Or should centrists now seize the chance he offers to address America’s dysfunctional status quo?

RFK is right to focus on chronic diseases, where America’s health lags far behind that of other advanced countries. He faces a war of attrition with malign forces, particularly Big Food and Big Soda, that have blocked so many sensible reforms in the past, and that are doing everything they can to influence the president. It is time for centrist Americans to hold their noses and join MAHA’s fight against chronic disease.

____

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Adrian Wooldridge is the global business columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. A former writer at the Economist, he is author of “The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments