Mary McNamara: Unlike 'The Baldwins,' Halyna Hutchins documentary grapples with reality of 'Rust' shooting

Published in Entertainment News

LOS ANGELES — Five minutes into the new Hulu documentary “Last Take: Rust and the Story of Halyna,” the film’s director, Rachel Mason, stands against the cornflower blue of the endless New Mexican sky.

“They airlifted her in the helicopter from right here,” Mason says, “and she died in the sky at this exact time.” As Mason continues speaking, images of Halyna Hutchins fill the screen — messing around on a Razor scooter, hiking with her family, riding horseback on the set of “Rust,” playing on the beach. “The last time I saw her, we were hiking with our kids. Halyna and I were friends. We were both filmmakers and moms. She came here to Santa Fe and never came back.”

Though brief, it is the type of footage one would expect to see at a memorial service, which, in essence, is what this film was supposed to be.

“After Halyna died,” Mason continues, “her husband Matt asked me to make a film about her life. But,” she adds, “I realized I couldn’t make a film about her life if I didn’t understand how she died.”

And therein lies the difficulty of any attempt to pay tribute to Hutchins’ life without it being overshadowed by the nature of her death, at least for commercial purposes. Tragically, the world knows Hutchins almost solely as the cinematographer who was fatally shot in October 2021 by a live bullet round discharged from a gun held by film star Alec Baldwin during a rehearsal for a scene in “Rust,” a low-budget Western.

Her death, and the wounding of director Joel Souza by the same bullet, dominated headlines for months in part because it should have been impossible. Multiple people on any film set are tasked with ensuring that no live ammunition is anywhere near guns used to tell cinematic stories. How it happened has been the subject of deep reporting by journalists, police investigators, forensic specialists, industry safety experts, and a series of criminal and civil court cases.

Those who followed that reporting, in The Times or elsewhere, will find little new information in “Last Take.” But with powerful, previously unseen footage and moving interviews with cast and crew, including some as they finally finish “Rust” more than two years after Hutchins’ death, the film more than makes up for that in context.

That especially includes footage and memories of Hutchins. Even if, as Mason admitted in a recent screening, the film was steered in a more sensational direction by those funding it, Hutchins remains the central character.

There is no villain in “Last Take.” From first glance, it is eminently clear that then-24-year-old armorer Hannah Gutierrez-Reed, now serving 18 months for involuntary manslaughter, should never have been hired to oversee the film’s many weapons, especially while also serving as prop master. Assistant director David Halls, who appears in the film, was supposed to double-check the weapons; still clearly guilt-stricken, he accepted a plea bargain and was convicted of negligent use of a firearm. Baldwin, who does not appear in the film, had his involuntary manslaughter charge dismissed due to withheld evidence.

But it does have a hero. In interview after interview, Hutchins is described, by friend and temporary colleague alike, as an inspired and committed filmmaker and an empathetic boss and co-worker. When speaking of her, they often become emotional, remembering her kindness and dedication.

As was first reported in The Times, the day before the shooting, members of the crew had walked off the set citing safety concerns. When Hutchins found out, ”she looked blindsided,” says crew member Jonas Huerta (identified in the film, as all interview subjects are, by only his first name.) “She said, ‘I feel like I’m losing my best friends.’”

The departing crew assumed their absence would cause filming to halt while producers dealt with the issues they had raised. Instead, production continued; Hutchins was attempting to make do when she was shot.

“I heard her monitor wasn’t working,” says Huerta, his voice shaking, “and she had to see the frame from the steady cam. … If I was there I could have put her monitor out of harm’s way. I always made sure she was out of the danger. Any time the gun was pointed, I would make sure that monitor was safe.”

Hutchins was the victim of a series of bad decisions, carelessness and at least one remaining mystery: how live bullets came to be on the set of “Rust.” “Last Take” reminds us of what was lost that day in New Mexico: A bright and talented woman, and a beloved mother, wife and friend, who had much of her life and career ahead of her.

It also provides a necessary balance, if not antidote, to “The Baldwins,” a TLC reality show that premiered last month.

Showcasing the lives of Alec and Hilaria Baldwin and their seven children, “The Baldwins” opens in the weeks leading up to Baldwin’s criminal trial last summer. Immediately after the shooting, and in the years that followed, he rigorously denied pulling the trigger of the gun that killed Hutchins, and said he was pointing it at Hutchins by her own direction in order to line up the shot on camera.

Many, including Hutchins’ widower Matthew, felt that Baldwin‘s refusal to acknowledge any responsibility in Hutchins’ death has been both disingenuous and unseemly. Matthew and his son sued Baldwin, reaching an undisclosed settlement nearly a year after the shooting. In 2023, Hutchins’ parents and sister also sued the actor, the film’s producers and the production company, Rust Movie Productions; lawyers representing the family told the presiding judge they will depose Baldwin in May.

None of that is addressed during the first two episodes of “The Baldwins,” in which the narrative is driven almost entirely by Hilaria Baldwin. Describing the toll the shooting — a word also never used — has taken on her husband, herself and their family, Hilaria Baldwin has a near-manic (she says she has ADHD) determination to make their home life as normal as possible. (I’m not sure exactly how she thought a camera crew would help achieve this.)

Baldwin, meanwhile, spends the first two episodes lurching around his spacious Hamptons home in a discernible daze, making random attempts to engage with his children, repeatedly praise his wife, and discuss the negative trajectory of his career all while clearly contemplating the very real possibility of a prison sentence.

With seven children under the age of 12, life most certainly had to go on in the Baldwin house, even in the countdown to trial. And no doubt Hilaria has been torn between ministering to her husband and her children. It is not a situation one would wish on their worst enemy.

But why the Baldwins, or anyone really, would think that the solution to this was participation in a reality show is beyond me, particularly the decision to film the weeks leading up to the trial. Hutchins is dead and Alec is ... complaining about losing work and having to be digitized for video games?

The third episode, which dropped Sunday, offers some clarity if not much in the way of self-awareness. Footage from the trial is prefaced by a brief explanation of the shooting, including pictures of Hutchins and Souza. After a teary-eyed Alec hears the judge dismiss the case, with prejudice, we learn that due to the pending appeal (during which the judge subsequently upheld her original judgment) and the various civil suits, he is not allowed to discuss the case.

He is allowed to discuss his feelings, however, which appear to be a cautious sense of relief and a desire to devote himself to raising his children. Hilaria finally gives voice to the obvious — that unlike Hutchins’ son, the Baldwin children still have both their parents. But if Baldwin seems content to take one day at a time, his wife wants them to start pushing forward. She encourages her husband to join her in therapy along with, I very much regret to report, “The Baldwins” camera crew.

Baldwin most certainly needs therapy, but it’s difficult to think of a more narcissistic, and potentially psychologically damaging, move than to have it filmed for a reality show. Especially when one of Baldwin’s first complaints is the toll that living a very public life has taken on him.

Here’s a thought: Don’t do a reality show.

With Baldwin unable to discuss the actual source of his obvious trauma — the fact that the gun he held shot and killed Hutchins — what, really, is the point? I certainly don’t want to hear any more about how his OCD interacts with Hilaria’s ADHD.

The fact that they are being paid to do this, with all the trappings of every parents-under-stress reality show, only adds to the air of self-centered exploitation.

As Mason says at the beginning of “Last Take,” Halyna Hutchins went to Santa Fe to make a movie and never came back.

That’s the reality. Maybe the Baldwins should take a break from filming and watch.

———

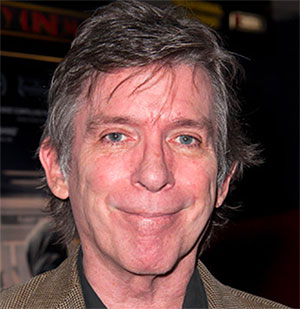

(Mary McNamara is a culture columnist and critic for the Los Angeles Times.)

———

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments