Trump's speedy appeals put Supreme Court on tricky path

Published in News & Features

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court’s special sitting for oral arguments Thursday exemplifies a balancing act the justices face in the second Trump administration, as the president and his allies in Congress criticize the courts that have stood in the way of his push to reshape the government.

Since the start of his second term, the federal courts have served as the main speed bump for President Donald Trump’s preferred policies, with the government counting more than two dozen nationwide injunctions from lower courts across more than 100 lawsuits over administrative actions.

Those cases, like Thursday’s arguments over the future of his effort to end birthright citizenship nationwide, are swiftly heading to the Supreme Court, which experts said will put the constitutional order in a pressure cooker.

Charles Geyh, a professor of law at Indiana University and former counsel for both the House Judiciary committee and the Administrative Office of U.S. Courts, said the slew of emergency applications follows a wide-ranging agenda from the president to assert maximum power and pits the justices against their own lower courts.

“They are dealing with a president that is taking unprecedented steps to centralize his power, and it is putting the court in an impossible situation, where they are concerned with legitimacy generally, but also they are concerned about the legitimacy of their orders,” Geyh said.

The Trump administration has filed more than a dozen emergency applications at the Supreme Court to overrule temporary lower court orders prohibiting the firing of members of the National Labor Relations Board, preventing a ban on transgender service members in the military, and an order restarting foreign aid payments.

Several of those are still pending, adding even more of a crunch to the conclusion of the term, when decisions in regularly scheduled cases are released by the end of June.

The justices have so far ruled in Trump’s favor in most of those emergency cases, with a few notable exceptions: continuing $2 billion in foreign aid payments the administration attempted to cancel; and ordering the administration to “facilitate” the return of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a migrant living in Maryland who the administration said it had mistakenly deported to an El Salvador prison despite a court order.

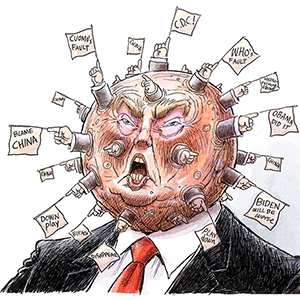

Trump himself has chafed at the courts’ rulings restricting his administration’s deportation push, which served as a major focus of his reelection campaign.

“Our Court System is not letting me do the job I was Elected to do. Activist judges must let the Trump Administration deport murderers, and other criminals who have come into our Country illegally, WITHOUT DELAY!!!” Trump posted on his social media site Truth Social last week.

Aziz Huq, a law professor at the University of Chicago Law School, said there are several risks for the justices in handling the emergency cases, such as being seen as enabling the Trump administration or being perceived as “trimming their own sails” to avoid a confrontation with another branch of government.

“I don’t think anyone knows how it will all play out, and I’m a little suspicious when people say they do know,” Huq said.

Geyh said that the way the court handles these cases, and the Trump administration’s reactions to them, could precipitate a constitutional crisis. Geyh pointed out that the U.S. Marshal Service, which answers to Trump, enforces judicial orders, and members of the administration like Vice President JD Vance have raised the possibility of defying court orders.

“The ultimate worry that has been with them for 200 years is now coming to pass,” Geyh said.

Congress and lower courts

Many of the emergency applications to the Supreme Court in recent months have come with some political baggage. Rulings from lower court judges in those cases and others have sparked calls from Trump and his close allies to impeach judges who rule against the administration.

Trump’s House allies have introduced at least four sets of articles of impeachment against judges in cases against Trump.

Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., said earlier this month that impeachments “are never off the table if they’re merited” but that it was unlikely the Senate would have the votes without a “brazen” crime.

He pointed to a bill from Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif., as a potential way to address injunctions. The measure passed the House earlier this year.

Separately Johnson said the House could pursue cutting funding for courts that rule against the administration.

At a House subcommittee on appropriations for the Judiciary hearing Wednesday, Robert J. Conrad, a former federal judge and director of the Administrative Office of U.S. Courts, criticized attacks on the judiciary and threats to impeach judges.

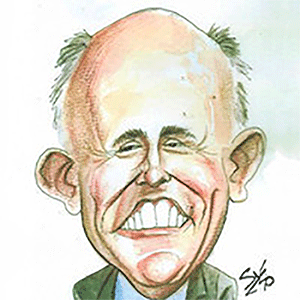

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. has spoken out multiple times about attacks on the judiciary in recent months, though he has never mentioned Trump or Republicans by name.

During an appearance at Georgetown Law on Monday, Roberts said the rule of law is “endangered” and warned against criticism of the justices.

“The notion that rule of law governs is the basic proposition,” Roberts said. “Certainly as a matter of theory, but also as a matter of practice, we need to stop and reflect every now and then how rare that is, certainly rare throughout history, and rare in the world today.”

Congressional Democrats have largely praised the courts’ actions so far. House Judiciary ranking member Rep. Jamie Raskin, D-Md., said that lower courts have done well with the “deluge” of litigation surrounding the Trump administration.

“And the Supreme Court has basically been standing up for due process, which is the linchpin of the whole Constitution,” Raskin said.

Off ramps

Huq and others said that even if the justices were to rein in the use of nationwide injunctions as part of the cases argued Thursday over birthright citizenship, it might not reduce the number of emergency cases that make their way to the Supreme Court.

Giancarlo Canaparo, a senior legal fellow at the Heritage Foundation, said that removing nationwide injunctions from lower court judges would remove some of the pressure for the justices to intervene, but it would be unlikely to reduce the number of cases that make it before them.

“The stakes would be lower but the litigation would proceed with as much speed,” Canaparo said.

Huq pointed out that there are other types of suits, such as those brought over spending freezes or those brought by multiple states, that could still bring high-pressure litigation to the justices.

It’s also a consequence of the court’s decisions in recent years that critics said aggrandized the court’s role in American politics, Huq said.

“The court has elicited a situation where that is likely to happen by setting itself up as the decider of all questions of public importance,” Huq said.

_____

©2025 CQ-Roll Call, Inc., All Rights Reserved. Visit cqrollcall.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments