Idaho's $200,000 in execution drugs expire in latest setback to death penalty

Published in News & Features

BOISE, Idaho — Idaho’s prison system once again is without execution drugs after its stockpile expired earlier this year, the latest in a series of hurdles to carrying out the death penalty in the state.

The Idaho Department of Correction has spent $200,000 in state funds on the hard-to-find lethal injection chemicals since 2023, according to public records obtained by the Idaho Statesman. But repeated delays, including prisoner appeals, have resulted in expiration of the drugs available to prison officials and left taxpayers footing the bill, Josh Tewalt, IDOC’s former lead executive, said in a recent court filings.

“Given prior delays in the state’s attempts to enforce its death penalty laws, IDOC does not want to purchase the chemicals necessary to carry out … execution by lethal injection until a death warrant is issued because those chemicals are expensive and have a short shelf life,” Tewalt said in a signed declaration.

Prison officials are “confident in our ability” to buy more execution drugs “should the need arise,” but they do not have any in their possession, IDOC spokesperson Sanda Kuzeta-Cerimagic confirmed to the Statesman. The department’s prior lethal injection drug purchases were a total financial loss to the state.

“There is no return policy on the chemicals, similar to how prescription medications are nonreturnable — but they remain necessary for the state,” Kuzeta-Cerimagic said.

This year, the Idaho Legislature passed a bill to replace lethal injection with a firing squad as the state’s lead execution method. The new law signed by Gov. Brad Little does not take effect until July 2026, providing time to IDOC to renovate its execution chamber to accommodate that method of capital punishment.

Last month, a federal judge in Idaho blocked all executions in the state until IDOC expands access to witnesses, including members of the media, to a concealed room where lethal injection drugs are prepared and administered during that type of execution. The court’s decision came in response to three news outlets, including the Statesman, suing the state prison system for preventing execution witnesses from seeing and hearing what happens in the room next to the execution chamber in past lethal injections.

‘Anonymity circumvents oversight processes’

For several years, Idaho prison officials searched but were unable to obtain lethal injection drugs because pharmaceutical manufacturers increasingly refused to sell them to prison systems for use in executions. IDOC resorted to paying cash for drugs from less regulated compounding pharmacies in neighboring states with questionable regulatory histories for the two most recent Idaho executions, in 2011 and 2012.

“Compounded pharmaceutical preparations used for lethal injection do not have a sufficient level of guidance to ensure they meet acceptable standards for use in this criminal procedure,” Dr. Jim Ruble, an attorney and longtime doctor of pharmacy who teaches college law and ethics courses in Utah, told the Statesman.

But those supplies soon dried up as well. Idaho lawmakers responded as other states did and passed a bill that Little signed in 2022 to grant anonymity to potential sellers to restart the flow of execution drugs for the state.

The new law was opposed by advocates for public transparency, including the Idaho Press Club and American Civil Liberties Union of Idaho, and also drew criticism from legal and medical experts. Such statutes may contribute to the inflated costs for drugs intended for executions, and greater questions about their safety, Ruble said.

“Anonymity circumvents oversight processes intended to validate the preparations are created within accepted standards,” he said.

Even then, prison officials could not immediately find lethal injection drugs, and IDOC was forced to postpone an execution scheduled for late 2022. That changed in the fall of 2023, however, when IDOC finally secured the powerful sedative pentobarbital to move forward with a lethal injection. The price was $50,000, a purchase order showed.

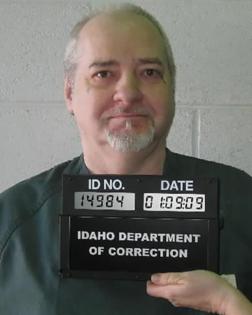

In February 2024, prison officials tried but failed to execute Thomas Creech, 73, incarcerated for nearly 50 years, when the execution team struggled for about an hour to locate a suitable vein in his body for an IV. They expended most of the costly drugs in the preparation process, which required purchase of another batch to plan for a second execution attempt of Creech.

The next round of pentobarbital cost the state $100,000, public records showed. Creech has remained in legal limbo since that time, including under a current federal stay of execution, and the latest batch of drugs expired in October 2024, according to an IDOC chain-of-custody form released in court filings.

In both circumstances, the hand-off of drugs to overseeing prison leadership took place on a rural stretch outside the gates of the prison complex south of Boise, Warden Tim Richardson said in a sworn deposition earlier this year.

“It’s just so you can not have, I guess, a visual on what you’re doing,” said Richardson, who was warden of the state’s maximum security prison at the time.

NBC News was first to report on the location of Idaho’s recent lethal injection execution drug pickups.

Other death penalty states spend big, too

When the state’s second batch of execution drugs expired, IDOC bought a third round of pentobarbital in October 2024, the court filings showed. That next round of chemicals then expired in February, court filings showed.

A purchase order obtained by the Statesman through another public records request revealed the price of those drugs at $50,000. That brought the total cost over the past two years to $200,000 for three rounds of pentobarbital, needed to meet the guidelines of the state’s lethal injection protocols.

Corrections departments are made to pay heightened costs from suppliers other than manufacturers because drug makers continue to decline to sell them for use in executions. Several other U.S. states with capital punishment have paid above and beyond what Idaho has for pentobarbital in recent years, according to news reports and court filings.

Utah spent $200,000 for the pentobarbital it used in an August 2024 execution, court records showed. Meanwhile, Tennessee paid nearly $600,000 for the drug over the past nine years, The Tennessean reported, while Indiana earlier this year acknowledged spending $900,000 for pentobarbital, according to the Indiana Capital Chronicle.

It is unclear how much of the the drug Tennessee and Indiana obtained in those purchases. The expected cost for a single round of pentobarbital per Idaho’s protocols is about $16,200, according to a signed declaration from a doctor of pharmacy filed by Creech’s attorneys in federal court. Three rounds would equate to about $49,000 on the retail market.

To limit future waste, IDOC revised its lethal injection preparation policy so pentobarbital is not loaded into syringes until it is certain a prisoner’s veins are ready to receive the drugs for an execution, Kuzeta-Cerimagic said. The change followed the failed attempt to execute Creech last year.

In addition, Tewalt said in his declaration, IDOC has changed course to wait to buy more lethal injection drugs until a death warrant has been served to a prisoner, which starts a 30-day clock for their scheduled execution. When the state transitions next year to a firing squad as its primary way to carry out the death penalty, lethal injection will be the backup execution method.

Idaho counts nine prisoners on its death row — eight men and one woman, all convicted of murder. Creech, now 74, and Gerald Pizzuto, 69, are the two prisoners in recent years to be issued repeat death warrants, but each is on a stay of execution for the time being after decades of incarceration.

The cost to house a prisoner on death row in Idaho is about $36,500 per year, according to IDOC.

©2025 Idaho Statesman. Visit at idahostatesman.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments